The National Parks Road Trip That Brought My Family Home

One writer tells the story of how her family traveled across the country, visiting national parks and fulfilling their dreams of America.

Jennie Baird

In 1971 my parents came into a three-thousand-dollar windfall. They bought a late model station wagon and traded their S&H Green stamps for a propane stove, two canvas tents and some sleeping bags.

It was my mother’s idea. She’d grown up in Brooklyn listening to Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, watching Westerns with Roy Rogers and Gene Autry. She had an idea of California, wanted to see the Pacific Ocean, to travel across the country she lived in and experience it firsthand. But my father, a Holocaust survivor who’d arrived in New York as a teenaged refugee, hated to leave home and after two years in the Panama jungle with the U.S. Army, he’d had enough of the great outdoors for a lifetime.

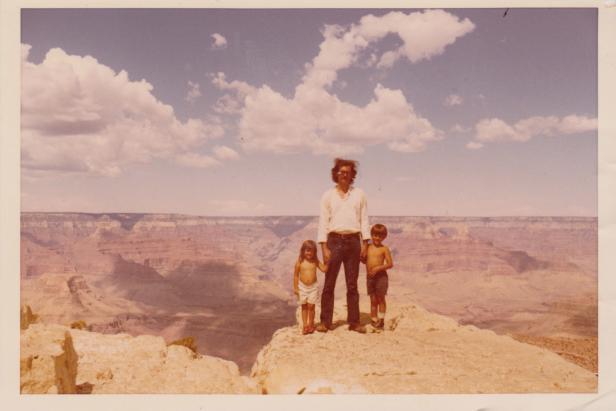

A teacher with summers off, he eventually capitulated and on a bright July day when I was three years old and my brother was five, we set off across America with only two rules: Wherever we went, we would visit the biggest tourist attraction and whenever possible, we would camp in the national parks.

Our trip began inauspiciously with our gear tumbling from the roof of the car as soon as we hit speed on the highway. Honest packing ineptitude or my father’s sabotage? I’ll never know. The plastic pages of vinyl-covered photo albums tell the story of our seven-week adventure: We pitched camp amid the dusky buttes of the Badlands and the Painted Desert; hiked the steep hollow of the Grand Canyon; rafted the Tetons’ Snake River with my brother at the rudder. In Yosemite, my quick-thinking dad—with the aid of two clanging pots—even chased off a bear who’d wandered into our tent site.

As we traveled across the country, we saw that, unlike the monuments of my father’s native Europe, America’s monuments are the land itself. Inspired by the majesty of the land that shaped our nation’s history and the parks system that reflected its values, my parents vowed to continue their national park experience closer to New York. The following summer, they set up camp for two weeks at Seawall in Acadia National Park, establishing a family tradition that would last generations.

As we traveled across the country, we saw that, unlike the monuments of my father’s native Europe, America’s monuments are the land itself.

In Acadia, we discovered not just the major attractions like Thunder Hole and Sand Beach, but also our own less famous favorite places – the tidepools of Wonderland where we raced periwinkles on wide tracks of kelp, the footbridges across Jordan Stream on the carriage roads where we played “billy goats gruff,” the gemstone of a glacial pond between the peaks of Sargent and Penobscot Mountains, its shimmering surface sliced by sweaty hikers and their shrieks of delight. At night we watched shooting stars from the seawall or attended ranger-led “amphitheater talks” at the campground. I’d often insist on staying awake until Ranger Foster came by calling for quiet hours with a wave of his flashlight.

Over the years, cousins, grandparents and friends from home visited us during our two-week stays on Mount Desert Island and many also joined the community of Acadia regulars. My baby sister, who would later work as a park ranger for a few years after college, celebrated her first birthday in Acadia, and in my twenties, after replicating my parents’ cross-country road trip on my own (three times), I got married on the rocks at Wonderland.

Now, forty-five years since my family’s epic road trip, I travel to Acadia regularly with my own children who are practically grown-ups themselves. On a mother-daughter holiday with my seventeen-year-old last summer, I was reminded of the unlikely friendships that develop in campgrounds. Although campsites themselves can be surprisingly secluded, it’s nearly impossible not to meet fellow campers at water spigots and “comfort stations,” (that’s national park speak for bathrooms). A conversation through the froth of toothpaste can easily evolve into an invitation to toast marshmallows at a neighbor’s campsite. The parks’ easy camaraderie is the byproduct of an implicit trust shared among people when no one has a front door to lock and the treasured land belongs to us all. A natural respect for each other’s property, space and quiet time is built into the parks’ ethos.

My parents, now 75 and 80, retired their tent a few years ago, but continue to travel to Mount Desert Island each summer, staying at the Seawall Motel, just outside the park’s entrance. With the wisdom of experience, they know that visiting every national park is the opportunity of a lifetime. But, especially for my dad, who still hates to travel, finding one that feels like home is even better.

.jpg.rend.hgtvcom.231.174.suffix/1674758726773.jpeg)